The Climate Signal in Insurance Markets

There is a lot to criticize about the insurance market. It’s often too concentrated, leading to monopoly pricing. It’s raising premiums faster than many ratepayers can keep up. The health insurance market, in particular, has earned its share of ire, which took a vengeful corporeal form a year ago. But there’s one thing about the insurance market that often goes unappreciated. It’s a machine for predicting the future. Not specific events — anyone who says they can consistently predict specific major events is either a fool or a charlatan. But in the aggregate, the insurance market is a system for taking big data and processing it into risk tables for anything anyone may wish to protect themselves against. It’s the effectiveness of this machine that allows us to use insurance prices to predict the effects of climate change in specific and useful ways. It’s also the rationality of actuarial science that makes the insurance system vulnerable to climate shocks before they happen, allowing it to act as a canary in the coal mine that may cause a major financial crisis within our lifetimes.

First, let’s think about insurance in the aggregate. Insurance companies calculate the total damages likely to occur in the future to a particular slice of the population. They then offer policies to cover these damages for slightly more than the expected value of the policyholder’s losses. Since expected values rarely occur exactly, many policyholders pay more than they gain and many gain more than they pay, but they no longer have to worry about the volatility of their damages. The fortunate policyholders subsidize the unfortunate each year, though the next year they may be the unfortunate.

From the company’s perspective, the problem is how much total damage is likely to happen in the future to a subset of customers, and how small they can make that subset. They gain revenue from premiums and take losses as covered damage occurs. If they calculated covered damage correctly, it is less than their revenue, so the average policyholder paid more than the average payout. If the market is competitive, the price of coverage must be as low as possible to undercut competitors. In a theory-land insurance market — perfectly competitive with perfect information, zero transaction costs, and risk-neutral insurers — the present value of premiums equals the present value of expected claims, plus administrative costs. Economic profit is zero in expectation. Since profits and survival depend on the accuracy of predicted damages, competition pushes insurers toward increasingly accurate pricing over time.

This depends on competitiveness and other assumptions, which can reasonably be questioned. When sectors or regions are monopolized, premiums will be inflated over predicted damages, and incentives to innovate in prediction may be reduced. But even in steady-state monopolization, especially when companies remain competitive elsewhere, premium prices can still reveal trends in future damages. For now, we set aside these complications and assume markets are broadly competitive.

Say we want to know the amount of home damage a town is likely to sustain in the next five years. Add up the homeowner’s insurance contracted for the next five years. That total is a rough estimate. If the amount paid to a company is lower than the damages it must pay out, it incurs a loss and must raise prices or exit. If the amount paid is too much more than the amount paid out, rates will be bid down. This method can be used to make granular predictions. What’s the expected value of flood damage in Kansas this year? Look at the amount being paid in flood insurance. Is a town in Florida likely to sustain more hurricane damage? If hurricane premiums are rising quickly, probably. Is a neighborhood facing worsening wildfire danger? Watch the price of wildfire insurance.

If we remove the assumption of competitiveness, this still largely holds, especially when using changes in premiums as a predictive tool. The raw amount owed in premiums may include monopoly rent and be higher than predicted damage. But both competitive and monopolistic markets respond to increases in expected damage in the same direction: by raising premiums.

Insurance predictions are impersonal and profit-driven. They reflect probabilities, not hopes. When damages are coming, it first shows in insurance markets. That’s why it’s alarming how they’re fleeing.

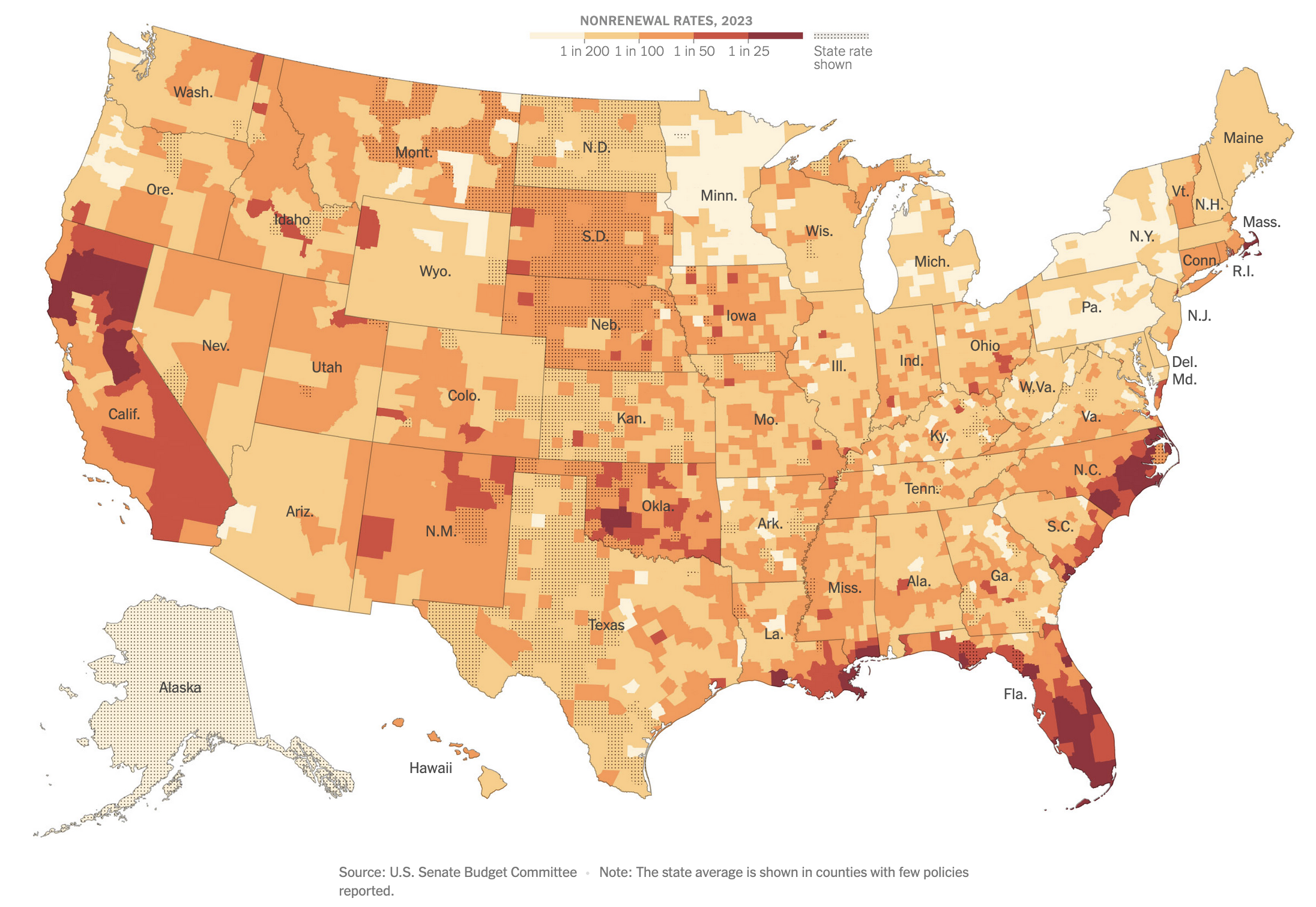

This map, from the Senate Budget Committee via this New York Times article, shows homeowner’s insurance nonrenewal rates in 2023. Red areas are those where over 1 in 25 policies were not renewed in that year alone. These are places insurers are exiting. They line up with areas at risk of hurricanes, wildfires, drought, and other disasters expected to worsen.

When an area becomes effectively uninsurable — when insurers withdraw or offer premiums homeowners cannot afford — it signals that expected losses are high relative to what residents can pay. In aggregate terms, the total damage predicted exceeds the politically or economically tolerable premium base. One of the most sophisticated risk-pricing systems our economy has built is signaling that losses may outstrip affordable coverage. Many of these areas are heavily populated.

The disaster hasn’t happened yet. But once insurers want out, the consequences begin in the present. Uninsurable homes become toxic assets. Banks require insurance for mortgages. Without insurance, many buyers cannot get financing. Most buyers need mortgages. An uninsurable house therefore loses most buyers. Its price falls, sometimes sharply. Homeowners can end up with a mortgage worth far more than the house. Defaults rise.

The insurance nonrenewal crisis can become a mortgage crisis. Bank balance sheets hold mortgages tied to these homes. If prices fall and defaults increase, those assets lose value. We learned in 2008 how bad an abundance of risky mortgages can get, though today’s financial system has stronger backstops and different structures of risk dispersion.

This is a financial risk in the making. There’s also the question of what happens to millions of people in areas where home values fall and insurance disappears. Their primary store of wealth declines. Some will be forced to move. Others will leave voluntarily. Either way, large-scale displacement from increasingly uninsurable regions would strain labor markets, housing markets, and public services elsewhere. California and Florida offer early examples of this pressure.

On a small scale, the economy can rebalance. But if this occurs during a broader financial downturn, or at a scale too large to absorb smoothly, it becomes something closer to an internal displacement crisis.

We tend to think Americans cannot become refugees, especially inside their own country. But a surge of mortgage-defaulted households leaving high-risk regions, newly impoverished and competing for limited housing and jobs, begins to resemble one. Moving millions from increasingly unlivable areas while financial institutions absorb correlated mortgage losses would be destabilizing. Insurers have already cancelled 2 million policies in 2018-2023, and in Florida, one in three affected homeowners plan to move. For a vivid illustration of internal displacement under economic stress, read The Grapes of Wrath.

So, to review: the insurance market prices rising climate risk and withdraws from the most vulnerable regions. Homeowners face falling property values and potential displacement. Banks face concentrated mortgage risk. Then the physical disasters arrive in areas already economically weakened.

This price adjustment is, in one sense, rational. Instead of homes suddenly becoming worthless when destroyed, the insurance market gradually pulls future expected losses into present prices. But when expected destruction grows beyond what households can pay and insurers can sustainably cover, the mechanism itself strains. In doing so, it brings part of that future crisis into the present. It functions as a warning signal. Areas becoming uninsurable are areas facing severe long-term risk.

There is one more layer. Insurers buy insurance for themselves. Reinsurers insure the insurers. They model aggregate claims and sell coverage against them. Their pricing reflects stress in the system even earlier than primary insurers. Watching the health of the reinsurance market may therefore provide advance notice about the health of the insurance market.

These are multiple layers of prediction: rising premiums, nonrenewals, stress in reinsurance markets. Taken together with accelerating climate risk, they outline a plausible path toward mortgage stress, financial instability, and large-scale internal migration.

One mitigation strategy would be proactive buyouts or relocation programs in areas facing severe long-term risk. That would be costly and politically difficult. State insurers of last resort can help calm the situation, but they can’t remain solvent forever in these conditions. Absent coordinated action, adjustment is more likely to be disorderly, managed through emergency interventions after crises emerge. No one can know the precise timing. But if stress deepens in reinsurance markets, it would suggest that the broader storm is approaching.